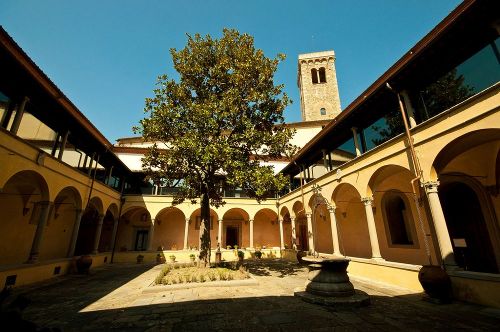

When I got accepted to the PhD programme at the European University Institute in Florence I was over the moon. It ticked all the boxes: A great university, a supervisor I looked forward to working with, an international environment, and a gorgeous location. I couldn’t be happier, and envisioned working together with colleagues from all over Europe with similar intellectual interests. My days would be filled with deep thinking and philosophising in a stunning setting, eating spaghetti for lunch and drinking copious amounts of Chianti with dinner. I got the food and scenery part about right, but my PhD path took a rather unexpected turn.

When I got accepted to the PhD programme at the European University Institute in Florence I was over the moon. It ticked all the boxes: A great university, a supervisor I looked forward to working with, an international environment, and a gorgeous location. I couldn’t be happier, and envisioned working together with colleagues from all over Europe with similar intellectual interests. My days would be filled with deep thinking and philosophising in a stunning setting, eating spaghetti for lunch and drinking copious amounts of Chianti with dinner. I got the food and scenery part about right, but my PhD path took a rather unexpected turn.

About three years into my PhD I fell suddenly and quite violently ill. After a late night, which included a couple of negroni’s (my cocktail of choice at the time) too many, I couldn’t quite remember how I got home. The next morning my stomach and head were spinning and I felt extremely exhausted. At first I thought I would just sleep it off, but my symptoms got worse instead of better. After a couple of days I decided to return to the Netherlands where I am originally from, to take a holiday and recuperate. Except recuperate I did not. I got worse, and ended up having to move in with my parents because I could no longer look after myself. Light and sound of any kind hurt, and I was too exhausted to even make it to the shops to buy basic supplies, or do anything much else. I could no longer read or watch TV for any length of time, and I was often too tired to have a simple conversation. It was absolute hell on earth. The doctors couldn’t find anything wrong with me, so they reasoned it must be a severe stress-related burnout. That sounded plausible as I had been under a lot of stress with the PhD, and hadn’t been coping well. (Now, almost 7 years later, I have found the culprit: it turns out to be late-stage Lyme disease. I have had it in my system for many years, but it decided to flare up and take over when PhD stress suppressed my immune system enough to allow it to).

About three years into my PhD I fell suddenly and quite violently ill. After a late night, which included a couple of negroni’s (my cocktail of choice at the time) too many, I couldn’t quite remember how I got home. The next morning my stomach and head were spinning and I felt extremely exhausted. At first I thought I would just sleep it off, but my symptoms got worse instead of better. After a couple of days I decided to return to the Netherlands where I am originally from, to take a holiday and recuperate. Except recuperate I did not. I got worse, and ended up having to move in with my parents because I could no longer look after myself. Light and sound of any kind hurt, and I was too exhausted to even make it to the shops to buy basic supplies, or do anything much else. I could no longer read or watch TV for any length of time, and I was often too tired to have a simple conversation. It was absolute hell on earth. The doctors couldn’t find anything wrong with me, so they reasoned it must be a severe stress-related burnout. That sounded plausible as I had been under a lot of stress with the PhD, and hadn’t been coping well. (Now, almost 7 years later, I have found the culprit: it turns out to be late-stage Lyme disease. I have had it in my system for many years, but it decided to flare up and take over when PhD stress suppressed my immune system enough to allow it to).

As I thought it was stress-related I set out to do everything I could to learn to handle stress better. Ever so slowly I improved. After eight months I moved into my own apartment. About two years after that, I found myself thinking about returning to the PhD programme. I was still too unwell to do much outside the house. Everything was overwhelming to my senses, and I was still terribly exhausted. But a bit of mental spark and stamina was returning. What if I could finish my PhD, working a little every day? There was only way to do it: by managing my energy in such a way that I would spend it on actually finishing my PhD, instead of going round in circles. When I was still in Florence I often spent my time worrying about my PhD (about 80% of the time), instead of doing the work (about 20% of the time). I am sure you can relate. I calculated that if I’d keep the same ratio in my present situation, I would have less than 10 minutes of time effectively spent on work. Although I had read a book called ‘Writing your PhD in 15 minutes a day’, I somehow doubted this was going to work. So instead, I decided to work on shifting my work-worry ratio to more satisfactory levels, and find ways to make the absolute most of my precious energy.

As I thought it was stress-related I set out to do everything I could to learn to handle stress better. Ever so slowly I improved. After eight months I moved into my own apartment. About two years after that, I found myself thinking about returning to the PhD programme. I was still too unwell to do much outside the house. Everything was overwhelming to my senses, and I was still terribly exhausted. But a bit of mental spark and stamina was returning. What if I could finish my PhD, working a little every day? There was only way to do it: by managing my energy in such a way that I would spend it on actually finishing my PhD, instead of going round in circles. When I was still in Florence I often spent my time worrying about my PhD (about 80% of the time), instead of doing the work (about 20% of the time). I am sure you can relate. I calculated that if I’d keep the same ratio in my present situation, I would have less than 10 minutes of time effectively spent on work. Although I had read a book called ‘Writing your PhD in 15 minutes a day’, I somehow doubted this was going to work. So instead, I decided to work on shifting my work-worry ratio to more satisfactory levels, and find ways to make the absolute most of my precious energy.

There was no grand master plan, and most of it I figured out through trial and error, but these were some of the most important shifts I made:

I had to learn to focus. I wanted to learn to better direct my energy so I could focus on what I wanted to focus on (working on my PhD) instead of being distracted. An important step for me in this process was to learn how to meditate and train my mind. When you meditate you practice experiencing thoughts and sensations, without reacting to them. When you learn to do the same in your daily life, you can let distractions be and float past more easily, and not succumb to their beckoning call. It becomes easier to direct your attention. Another important step was to stay well within my energy limits. So if I had 45 minutes of mental energy a day, I would not push myself to work longer than that. I would work for 45 minutes, be very proud of myself that I managed, and would then give myself the rest of the day off. Surprisingly, this simple habit of being strict about working less, instead of working more, caused a surge in my productivity. It shot up (even though it did not always feel that way at the time).

I had to learn to focus. I wanted to learn to better direct my energy so I could focus on what I wanted to focus on (working on my PhD) instead of being distracted. An important step for me in this process was to learn how to meditate and train my mind. When you meditate you practice experiencing thoughts and sensations, without reacting to them. When you learn to do the same in your daily life, you can let distractions be and float past more easily, and not succumb to their beckoning call. It becomes easier to direct your attention. Another important step was to stay well within my energy limits. So if I had 45 minutes of mental energy a day, I would not push myself to work longer than that. I would work for 45 minutes, be very proud of myself that I managed, and would then give myself the rest of the day off. Surprisingly, this simple habit of being strict about working less, instead of working more, caused a surge in my productivity. It shot up (even though it did not always feel that way at the time).

I had to learn to shift gears and let go. Instead of having the PhD hanging over me like a dark cloud every minute of the day, I had to learn to disengage. Again, meditation was brilliant. It really does help you free up mental space. What also helped was exercise. By getting into my body instead of staying stuck in my head, I would allow my mental energy reserves to be replenished. What I did most days was turn the music up after I had finished work and dance along for a couple of songs. Yoga was a great tool too. But most important of all: I gave myself full permission to let go, and let the PhD be until my next work session. I made a deep and conscious decision to let go and I congratulated myself on not working. When my energy levels increased I worked to keep implementing these lessons: focus and work hard for a set (and relatively short) amount of time. And then relax. It became my key practice.

I had to learn to shift gears and let go. Instead of having the PhD hanging over me like a dark cloud every minute of the day, I had to learn to disengage. Again, meditation was brilliant. It really does help you free up mental space. What also helped was exercise. By getting into my body instead of staying stuck in my head, I would allow my mental energy reserves to be replenished. What I did most days was turn the music up after I had finished work and dance along for a couple of songs. Yoga was a great tool too. But most important of all: I gave myself full permission to let go, and let the PhD be until my next work session. I made a deep and conscious decision to let go and I congratulated myself on not working. When my energy levels increased I worked to keep implementing these lessons: focus and work hard for a set (and relatively short) amount of time. And then relax. It became my key practice.

I had to learn to sustain effortless momentum. I could no longer push myself to do things, as I would pay dearly for it afterwards. I had to learn to work from a more effortless place. It’s so easy to lose touch with this sense of ease when doing academic work. There is an imbalance between effort exerted and immediate rewards, which I learnt is a recipe for producing feelings of stress and hopelessness. The fact that the academic model centres on criticism doesn’t help either. There is no better feeling in the world than nailing an argument, but the process of getting there can be disheartening. Academics are, by profession, experts in shooting down their own (and others’) work. It’s the nature of the job, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t affect us. To stay in a more positive place, I became more professional and self-appreciative in many ways. I became my own fiercest supporter. I decided I would be kind to myself. I would no longer say cruel or nasty things to myself in my head no matter what, and if anyone else decided to be less than nice to me, it would be their problem not mine. I also tried to work from a place of wonder and excitement. There was a reason I wanted to write this PhD, and I finished it from this place of curiosity.

I had to learn to sustain effortless momentum. I could no longer push myself to do things, as I would pay dearly for it afterwards. I had to learn to work from a more effortless place. It’s so easy to lose touch with this sense of ease when doing academic work. There is an imbalance between effort exerted and immediate rewards, which I learnt is a recipe for producing feelings of stress and hopelessness. The fact that the academic model centres on criticism doesn’t help either. There is no better feeling in the world than nailing an argument, but the process of getting there can be disheartening. Academics are, by profession, experts in shooting down their own (and others’) work. It’s the nature of the job, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t affect us. To stay in a more positive place, I became more professional and self-appreciative in many ways. I became my own fiercest supporter. I decided I would be kind to myself. I would no longer say cruel or nasty things to myself in my head no matter what, and if anyone else decided to be less than nice to me, it would be their problem not mine. I also tried to work from a place of wonder and excitement. There was a reason I wanted to write this PhD, and I finished it from this place of curiosity.

Naturally, I didn’t get all these things right all the time. It was an on-going process. But I was on to something. I managed to finish my PhD by working an average of 2 to 3 hours a day (and made all my deadlines!). My work was astonishingly well received. Now, I teach PhD students the same skills that helped me. I teach seminars, I coach people, and I have designed a 6-week online course to help PhD students write their PhDs more effortlessly. Unfortunately my health struggles aren’t over. But I hope others can benefit from the hard lessons learnt, without the sacrifice.

Naturally, I didn’t get all these things right all the time. It was an on-going process. But I was on to something. I managed to finish my PhD by working an average of 2 to 3 hours a day (and made all my deadlines!). My work was astonishingly well received. Now, I teach PhD students the same skills that helped me. I teach seminars, I coach people, and I have designed a 6-week online course to help PhD students write their PhDs more effortlessly. Unfortunately my health struggles aren’t over. But I hope others can benefit from the hard lessons learnt, without the sacrifice.

Thanks. I am going to sign up to your course. I can do this 🙂

Thanks Gemma. It is very hard to have a big gap between what you’d like to accomplish, and what you actually can accomplish in a day. I know all about it. It’s hard! And it’s frustrating. I still work at these practices daily – I try to spend the energy I have in the best possible way. Good luck with your own work – a couple of hours a day of being able to concentrate and work is plenty. Really. You can do it 🙂

This is such an uplifting piece. Thank you for writing. As someone who has several chronic conditions including M.E a lot of my time is spent either worrying about my work, or too exhausted/ in pain/ brain fogged. I have been doing a similar thing, chipping away each day, 7 days a week, even if I can only concentrate for a couple of hours.