In my experience academia can be a great place for someone with a chronic illness. That’s not to say it is easy – it really isn’t, but there can be a flexibility, particularly during the early years of a career, when research is the primary activity. The situation gets more difficult later on, when there is an expectation of taking on more teaching and admin responsibilities. This is my story.

I am not currently working, but for many years I worked in academia with a chronic illness. I became ill with ME half way through my PhD in Physics – yet I was lucky, I was mildly affected and able to complete all my experimental work and write up more or less on time. It was only when I started my first post-doc position a few months later in a new city 200 miles away that I realised how ill I was. When I started work I quickly saw that a full day was beyond me. Luckily my line-manager was extremely supportive, and we agreed that I would work 9:00am till 3:00pm and increase my hours when and if I was able – he took the view that so long as I ‘achieved’ academically (I guess that meant producing papers), then it didn’t matter how or when I did it. He also said he thought some people wasted a lot of time on coffee breaks! Somehow I did manage to keep publishing, although perhaps not as much as my colleagues.

I am not currently working, but for many years I worked in academia with a chronic illness. I became ill with ME half way through my PhD in Physics – yet I was lucky, I was mildly affected and able to complete all my experimental work and write up more or less on time. It was only when I started my first post-doc position a few months later in a new city 200 miles away that I realised how ill I was. When I started work I quickly saw that a full day was beyond me. Luckily my line-manager was extremely supportive, and we agreed that I would work 9:00am till 3:00pm and increase my hours when and if I was able – he took the view that so long as I ‘achieved’ academically (I guess that meant producing papers), then it didn’t matter how or when I did it. He also said he thought some people wasted a lot of time on coffee breaks! Somehow I did manage to keep publishing, although perhaps not as much as my colleagues.

Despite this I felt so guilty leaving work mid-afternoon – particularly if I left feeling anything other than completely wiped out. I also felt that everyone must be wondering why I was leaving so early. Years later I discovered that a close colleague had not only not noticed  that I left early, but was totally surprised when I told her I was ill – her exact words were ‘but you seem so energetic’! An important lesson here: most people are too busy focusing on their own lives to pay that much attention to what is going on in yours! The down side of this is that they only see you at your best – what they don’t see is how you are when you stop – the recovery time you need every evening and all weekend, just so you can get up on Monday morning and do it all again.

that I left early, but was totally surprised when I told her I was ill – her exact words were ‘but you seem so energetic’! An important lesson here: most people are too busy focusing on their own lives to pay that much attention to what is going on in yours! The down side of this is that they only see you at your best – what they don’t see is how you are when you stop – the recovery time you need every evening and all weekend, just so you can get up on Monday morning and do it all again.

At first it was incredibly tough – I was so exhausted that every activity needed incredible will power. I would talk to myself to get through each event ‘you just need to drive round this corner’, ‘ you just need to park the car’, ‘you just need to walk from the car to the office’. I would get home after work and fall asleep, sometimes not even making it onto the sofa but collapsing on the floor in the lounge. At work I struggled too – my brain processes information much slower than it used to. It would take what seemed like ages before I could decode the questions I was being asked, and much longer to work out a reply – often so long my line-manager had assumed that I didn’t know the answer. I had no idea how to bring this issue up.

At first it was incredibly tough – I was so exhausted that every activity needed incredible will power. I would talk to myself to get through each event ‘you just need to drive round this corner’, ‘ you just need to park the car’, ‘you just need to walk from the car to the office’. I would get home after work and fall asleep, sometimes not even making it onto the sofa but collapsing on the floor in the lounge. At work I struggled too – my brain processes information much slower than it used to. It would take what seemed like ages before I could decode the questions I was being asked, and much longer to work out a reply – often so long my line-manager had assumed that I didn’t know the answer. I had no idea how to bring this issue up.

What really helped was being able to plan my own day. This is where academic research is often a great place for people with chronic illness. I could alternate between doing practical work in the clean-room, and thinking type work at my computer. Eventually, I was able to increase my hours a little and even have a social life! For many years this seemed to work. I even got a new job and moved cities again. At my interview I simply told my new employers about my illness and kept my fingers crossed that my academic  record would win through. Then I got a promotion – a five-year fellowship in bio-nano-technology! After endless short-term contracts I had made it: a fellowship that would almost certainly lead to a lectureship, the Holy Grail of academia. I worried how I would meet the demands of the job, particularly the teaching, which, although enjoyable, was far more demanding on my energy levels. I also had a slightly longer commute, and after a bad bout of flu and struggling on for 18months the inevitable happened: I crashed. The crash became a full-blown relapse, leaving me housebound, and over five years later there is only marginal improvement in my health. It seemed that my job and my hopes of an academic career had come to an end.

record would win through. Then I got a promotion – a five-year fellowship in bio-nano-technology! After endless short-term contracts I had made it: a fellowship that would almost certainly lead to a lectureship, the Holy Grail of academia. I worried how I would meet the demands of the job, particularly the teaching, which, although enjoyable, was far more demanding on my energy levels. I also had a slightly longer commute, and after a bad bout of flu and struggling on for 18months the inevitable happened: I crashed. The crash became a full-blown relapse, leaving me housebound, and over five years later there is only marginal improvement in my health. It seemed that my job and my hopes of an academic career had come to an end.

But there is another twist in this tale. I enrolled on a part-time masters degree, more to keep my brain active than to get a qualification. I chose to study e-learning, a course which, living up to its name, is delivered entirely on-line. This meant I could study as and when I was able (my experiences of studying with a chronic illness are discussed in more detail here). Then the unexpected happened – I fell in love! Through the course I discovered the field of Physics Education Research (PER) – an area which combines my background in physics with my interest in learning and teaching, without needing to spend hours in a dark lab or noisy clean-room. I have recently completed my dissertation in collaboration with the PER group in Edinburgh – and have found that I can do high-quality research from my sofa! I have submitted one paper for review and am preparing another. I feel like an academic again! The irony is that without this relapse I would probably never have discovered my passion for Physics Education Research, yet because of my illness I am currently unable to make it my full- time career.

But there is another twist in this tale. I enrolled on a part-time masters degree, more to keep my brain active than to get a qualification. I chose to study e-learning, a course which, living up to its name, is delivered entirely on-line. This meant I could study as and when I was able (my experiences of studying with a chronic illness are discussed in more detail here). Then the unexpected happened – I fell in love! Through the course I discovered the field of Physics Education Research (PER) – an area which combines my background in physics with my interest in learning and teaching, without needing to spend hours in a dark lab or noisy clean-room. I have recently completed my dissertation in collaboration with the PER group in Edinburgh – and have found that I can do high-quality research from my sofa! I have submitted one paper for review and am preparing another. I feel like an academic again! The irony is that without this relapse I would probably never have discovered my passion for Physics Education Research, yet because of my illness I am currently unable to make it my full- time career.

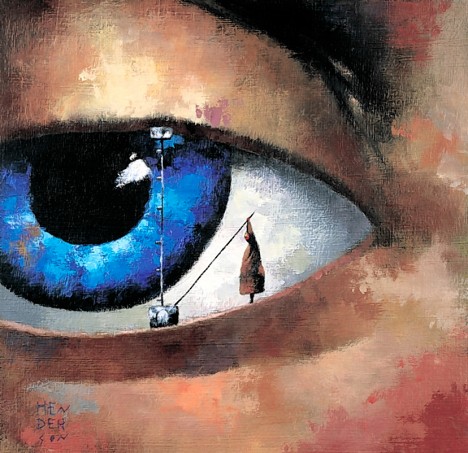

I don’t yet know what the future holds. I am at a crossroads. Re-entering the world of work with the level of illness that I have is practically impossible. There would need to be a flexibility and understanding that is non-existent outside academia and rare within it. So I am nervous that someone will offer me my perfect job, yet I can’t help hoping for it, wishing for it and pursuing it. I will keep going because the alternative – to give up on my dream and my passion, to be defined by the illness and not by what I can achieve – is far far worse.

I don’t yet know what the future holds. I am at a crossroads. Re-entering the world of work with the level of illness that I have is practically impossible. There would need to be a flexibility and understanding that is non-existent outside academia and rare within it. So I am nervous that someone will offer me my perfect job, yet I can’t help hoping for it, wishing for it and pursuing it. I will keep going because the alternative – to give up on my dream and my passion, to be defined by the illness and not by what I can achieve – is far far worse.

Hi Anna. I admire your tenacity in attempting to hold To your career…let alone improve it. I was inYour position for ten years after getting ME …I struggled to work and study to progress my career. However after completng my last exam in 2002 I collapsed and relapsed e ven worse than previous and has an added diagnosis of Fibromyalgia to contend with…all of which is still with me. I attempt to do a two year training course

in business and IT but relapsed again without completing all modules. That was six years ago and im loathe go put my toe in The water again. I have found that jn the past two years ive started a regime of supplemets developed by Dr Wilson (us)…they ard called ADRENAL REBUILDER .SUPER ADRENAL STRESS FORMULA and Adrenal C formula and Herbal Adrenal Support. I have found thesd formulas have had a very possitive effect on my energy and stamina since starting them. He has written a great book called Adrenal fatigue – a twentyfirst century problem. “. Good luck with your career plans. Therese x

You really are a remarkable person, Anna, and whilst I mourn that academic career for you which seemed almost within your grasp, I deeply respect your tenacity and determination and self-discipline. You are all kinds of awesome.