I realise that for many of you none of what I write here will be news. Especially in the social sciences and the creative arts, the practices that have in recent years become known as public or community engagement often have long been an integral part of research and other academic activities. However, I feel that in other disciplines, such as my own, public engagement is still occasionally seen as either some mythical thing, or as an unnecessary and irrelevant evil imposed by managerial and governmental monsters. It’s neither, at least for the purposes of this post and in my opinion, and I hope that this will become clear here.

WHAT IS PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT?

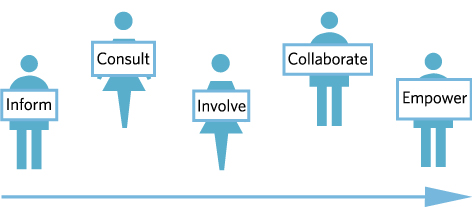

The term “public engagement”, according to The National Co-Ordinating Centre for Public Engagement (NCCPE), “describes the myriad of ways in which the activity and benefits of higher education and research can be shared with the public. Engagement is by definition a two-way process, involving interaction and listening, with the goal of generating mutual benefit” (see here).

Based on this definition, and for the cynics among you, it’s perhaps important to mention what public engagement is not:

– It’s not the equivalent of dissemination. Putting your research on flyers and handing them out is not engagement.

– It’s not you telling the “deprived public” of your “wonderful” work, which they should receive with admiration.

– It’s also not “dumbing down” your “sophisticated” research for the “less educated”.

So, on a more positive note, here is what public engagement is, or at least can be:

– It’s any practice that involves non-academic audiences in your research.

– It’s any practice that facilitates a two-way conversation about your research with non-academic audiences.

We will come to much more concrete examples of what these practices could look like in the final section of this post, so don’t feel lost in these more “abstract” explanations just yet.

WHY SHOULD YOU DO PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT?

So, why would you want to engage in any such activities? After all, you’re happy sitting in your study or the lab, reading books, thinking about stuff, writing some of it down (as Leonard Hofstadter from The Big Bang Theory puts it). Knowledge for knowledge’s sake is all very good, but why not share and open up that knowledge with those outside of that very limited circle of academics with whom you’re used to working? If you think that your research simply has no relevance to anyone beyond the confines of your lab, office, or study, you’re likely to be wrong (and I can’t help but wonder how you get out of bed every morning). So here are some brief reasons for why you should devise some public engagement projects relating to your work:

So, why would you want to engage in any such activities? After all, you’re happy sitting in your study or the lab, reading books, thinking about stuff, writing some of it down (as Leonard Hofstadter from The Big Bang Theory puts it). Knowledge for knowledge’s sake is all very good, but why not share and open up that knowledge with those outside of that very limited circle of academics with whom you’re used to working? If you think that your research simply has no relevance to anyone beyond the confines of your lab, office, or study, you’re likely to be wrong (and I can’t help but wonder how you get out of bed every morning). So here are some brief reasons for why you should devise some public engagement projects relating to your work:

– Other people may not have the access or specialist vocabulary to engage with it, despite being interested in it.

– Find them, talk to them. They can help you see your research and your communication of it differently.

– Do you feel your research contributes to society? This doesn’t happen on its own or behind journal paywalls.

– Do research with and for communities of people rather than just on them.

– If you are researching “them”, surely “they” are the best people to inform your focus and methods.

HOW CAN YOU DO PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT?

So you want to engage. You’re all fired up and ready to go. But where? Where is this ominous “public” with whom you’re supposed to engage? Well, you have to find it. Often this isn’t as difficult as it sounds. It can be a specific local community, you can get in touch with national or regional societies and unions, and so on. Think about what you want to do. Then make contact – all they can do is say no! But what, you may ask, am I supposed to do? What activities are useful and appropriate for my research area? The good news is that there are plenty of resources on existing engagement projects, no matter your discipline. The NCCPE is a great place to start. They have guides, and they also have ideas and lists of different methods of engagements which you may want to adapt for your own purposes.

So you want to engage. You’re all fired up and ready to go. But where? Where is this ominous “public” with whom you’re supposed to engage? Well, you have to find it. Often this isn’t as difficult as it sounds. It can be a specific local community, you can get in touch with national or regional societies and unions, and so on. Think about what you want to do. Then make contact – all they can do is say no! But what, you may ask, am I supposed to do? What activities are useful and appropriate for my research area? The good news is that there are plenty of resources on existing engagement projects, no matter your discipline. The NCCPE is a great place to start. They have guides, and they also have ideas and lists of different methods of engagements which you may want to adapt for your own purposes.

One approach which I find particularly inspiring mainly because it often involves the use of art, images, and writing, is what has become known as participatory research, although this practice brings with it a range of ethical issues you will want to consider in advance (see here for a great guide on the topic). Put simply, participatory research does what it says on the tin: it involves people from outside the academic community in research and in the creation of research outputs. One particularly inspiring example I’d like you to take a look at is one (of many) conceived by Professor Maggie O’Neill (Durham University), whose work has been concerned with migrants, asylum seekers, and sex workers in particular. The project is called “Women’s Lives, Well-Being and Community”, and you can find a brochure on its methods and outcomes here.

Public engagement can take many shapes, but here are some questions and prompts that may help you come up with your own project or approach:

– Rather than just doing interviews, can your participants produce something that tells their story?

– This could be art (you can work with art therapists, art teachers, etc.), photography, creative writing.

– Can your participants create something which can take on a life of its own beyond your research?

– Think of your research, but also of your participants. Your research is about, for and with them.

– Are the texts or authors on which you work interesting to a particular community?

– Can they create something which expresses their relationship to the texts?

– What are your participants’ feelings about the history of your subject?

– Again, can they create something based on this?

Very often, public engagement is about communicating research from very different perspectives, in a different language, and even in a very different format (including, especially, the visual image, in whatever form).

I would argue that participatory research is possible for any project, in any discipline, and even if I haven’t been very specific here, I do hope that some of the resources included in this post will motivate and inspire you to create your own project. It’s needless to say that any such project will require funds – be daring, ask your faculty, university, or apply for external funding. Public engagement and impact are a requirement by research councils in the UK, and a project which includes clear avenues for these activities will always look more attractive to funders (providing you have a sensible project and topic in the first place of course). So get out there and do it! I promise you’ll find it rewarding as well as useful.

Hi Nadine, it’s great to see PEAs in action! It’s especially great to see PEAs for arts and humanities. Coming from the sheltered world of science, where PE is established as it’s own practise , but still not widely accepted by academics, it’s really interesting to read how PE is coming off the ground in the Arts. I think you’ve done well in this article, summing up the salient points about how rewarding PE can be, and some of the benefits of properly engaging rather than performing.

Really glad you stress the participatory, two-way nature of good public engagement- I *always* learn from the audience when I run things, not least how to articulate my work clearly, and it helps me review what I think I’m doing! The most transformative event I ran was on my work on medieval nuns, for a convent of modern nuns. Their very different response to my findings helped me see my source material in a very different and possibly more authentic light, and their lived expertise, tho ‘non-academic’, stopped me from being quite so patronising!

My advice would be to echo that above- start off with a very specific audience rather than aiming at “the general public” whatever that is, with whom you can build a two-way relationship. Simple one-off youtube videos, audioclips, blogposts etc are great ways to start and can be developed with your identified specific audience- the early career researchers I’ve worked with so far have mostly wanted to race ahead, with complex web resources, hard-to-maintain blogs and BBC TV series. Just because the Internet can potentially reach everyone, doesn’t mean your resources necessarily will- start small and specific so you have a ready made audience and they can grow from there! I also like exploring Martin Weller’s notion of public engagement as ‘collateral damage’ – frictionlessly produced where possible, rather than major undertakings.

Great post Nadine- impact and public engagement are so much more than higher ed buzz-words and over the last year I’ve been amazed at the variety of types of public engagement that are possible. One really interesting e.g. of the kind of participatory research you mention is that of Karen Throsby who researches channel swimmers (I recently blogged about her here – http://blogs.warwick.ac.uk/researcherlife/entry/ace_event_impact/)

My key advice to early career academics is to think about starting small – podcasts, blogging, writing for non-specialist outlets, videos etc. are all great ways to start thinking about how you can communicate your work to different audiences, and will help you to build up media skills and a good portfolio that will stand you in good stead for putting together a bigger project.