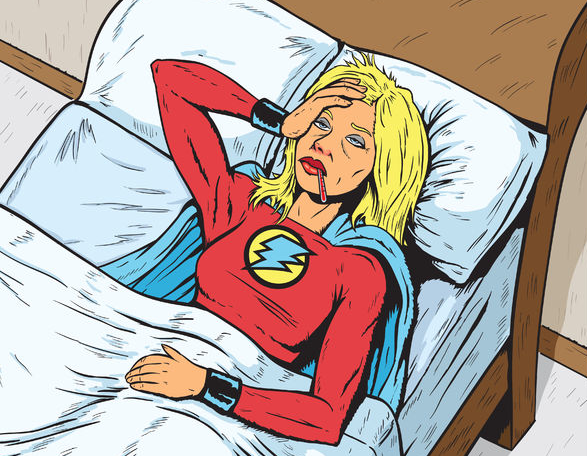

When you’re ill, do you keep calm and carry on, or do you keep calm and take time off? I’ve just come to the end of two weeks sick leave. Shingles seriously knocked me out, even though I noticed it and got anti-viral medication on the very first day the rash appeared. It was the first time in my life that I’ve had to take sick leave for more than a day, and this, alongside my line manager’s kind encouragement to not come back until I was definitely better and pain-free, got me thinking. How many days had I spent at the office and in the classroom being ill? How often did I encounter colleagues on the corridor who were battling through a bad cold? On how many research days at home did I insist on carrying on as if I wasn’t ill, wrapped in a blanket in my study, and with caffeine, painkillers, and tissues to hand? The answer – for me, and I suspect for many of you – is: a lot.

I find it scary how normal it has become for most of us to go to work despite being ill, and I wonder how many people consider the long-term effects on their (and other people’s) health this “keep calm and carry on” attitude has. It seems that in academia as well as in many other jobs it’s not even heroic to carry on as usual when you’re ill; it’s the new normal. In turn, I wonder how widespread the idea is that taking time off when you’re physically unwell is a sign of weakness, of failure, of a lack of dedication to your career, your company, or your cause.

I find it scary how normal it has become for most of us to go to work despite being ill, and I wonder how many people consider the long-term effects on their (and other people’s) health this “keep calm and carry on” attitude has. It seems that in academia as well as in many other jobs it’s not even heroic to carry on as usual when you’re ill; it’s the new normal. In turn, I wonder how widespread the idea is that taking time off when you’re physically unwell is a sign of weakness, of failure, of a lack of dedication to your career, your company, or your cause.

I felt incredibly lucky and relieved when my Head of Subject told me I should take the time off that I needed to get well again. Lucky and relieved because I almost felt guilty for having to say I wasn’t well enough to teach, and in my head the standard procedure is to just get on with things as if nothing was wrong.

From both an institutional and a personal perspective it was pointless to continue working because it would most likely prolong my illness in the short-term, and I suspect it would also impact on my long-term health, and not just because shingles can cause lasting nerve damage. I firmly believe that with every illness from which we ask our body to recover without giving it the rest it needs to do so fully and properly chips away at our longterm health, our immune system, and our general wellbeing. Going to work ill doesn’t only increase the risk of spreading whatever bug it is you’ve caught, but it also means wearing yourself down that little bit more each time.

In some jobs, including precarious hourly-paid teaching contracts, missing a day’s work – even due to sickness – means losing a fraction of a much-needed income. This wasn’t the case for me. Still, I was worried. I knew my classes would be covered by wonderfully capable colleagues who reassured me that I should rest up. Still, I was worried.

In some jobs, including precarious hourly-paid teaching contracts, missing a day’s work – even due to sickness – means losing a fraction of a much-needed income. This wasn’t the case for me. Still, I was worried. I knew my classes would be covered by wonderfully capable colleagues who reassured me that I should rest up. Still, I was worried.

In the beginning, I thought I’d be able to at least carry on marking from home when I wasn’t sleeping, but it quickly turned out that I’d be sleeping pretty much all day, and that when I wasn’t in bed the pain I was in certainly wouldn’t make for a good basis on which to grade my students’ first battles with literary and cultural theory. So I did nothing for two weeks. Well, almost nothing, or as close to nothing as I’ve ever come. I answered the odd email here and there, even though I had an out-of-office message set that explaining I was ill and would respond to urgent emails as soon as I could.

Overall, though, I rested, and I rested a lot. On average, shingles can last anywhere from 3-5 weeks (and longer), but after 12 days I’m pretty much symptom-free and back on my feet. I doubt that would have been the case had I schlepped myself into uni to do, among other things, my four hours of back-to-back teaching on a Thursday, for example.

My question is: why, when we know what our bodies need in order to be well, are we so reluctant to keep calm and take time off, instead of desperately carrying on? It’s inevitable that when we’re ill we’re not at our best in the classroom, or at admin and marking, or at research and writing. I’m fairly certain that the best work isn’t delivered with Lemsip stains on it. The benefits of battling through illness while continuing to work as normal are very few, if any, at least in your average sickness situation (with chronic illness being a whole different, difficult topic, as many of my guest bloggers have discussed). Yet, for a vast variety of reasons – from institutional pressures to internalised performance measures and for personal reasons – we seem to find it difficult to admit that sometimes the best thing we can do for ourselves and for others is to practice selfcare and rest up.

My question is: why, when we know what our bodies need in order to be well, are we so reluctant to keep calm and take time off, instead of desperately carrying on? It’s inevitable that when we’re ill we’re not at our best in the classroom, or at admin and marking, or at research and writing. I’m fairly certain that the best work isn’t delivered with Lemsip stains on it. The benefits of battling through illness while continuing to work as normal are very few, if any, at least in your average sickness situation (with chronic illness being a whole different, difficult topic, as many of my guest bloggers have discussed). Yet, for a vast variety of reasons – from institutional pressures to internalised performance measures and for personal reasons – we seem to find it difficult to admit that sometimes the best thing we can do for ourselves and for others is to practice selfcare and rest up.

So, to come back to my original question: do you keep calm and rest up, or do you keep calm and carry on? Under what reasons and what circumstances? Do you feel pushed to do one or the other? And, if so, why?

Thanks for this Nadine, and thank you for mentioning the impact sickness has on hourly paid lecturers. I was ill with cold/ flu etc a couple of weeks ago which luckily didn’t last long but unluckily started the day before my teaching day. I went in anyway because I couldn’t face the hit of losing over half of my income for the week, it also doesn’t help that my university at least isn’t very forthcoming in explaining what to do if you actually were too sick to come in.

Thank you for this very interesting post! When I am ill, I usually go to work. I work on a french university. If I am not here to teach, my students will have a free time… My colleagues are so overwhelmed that you can only organize a replacement, if it is planed. And, if I’d stay at home, I would have to organize other courses, in order that my students don’t miss anything. It is so hard to organize these, that it is easier, if I go to work, even if I feel very bad…