At a time when we remember the First World War, its victims, and its survivors, it seems apt for me to share some of the research I’ve been doing on the literary and cultural history of the widow in Britain, and particularly on how the state’s support and the economic conditions of widowed women has changed in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and reflects both Britain’s development in terms of gender equality as well as the emergence of the welfare state.

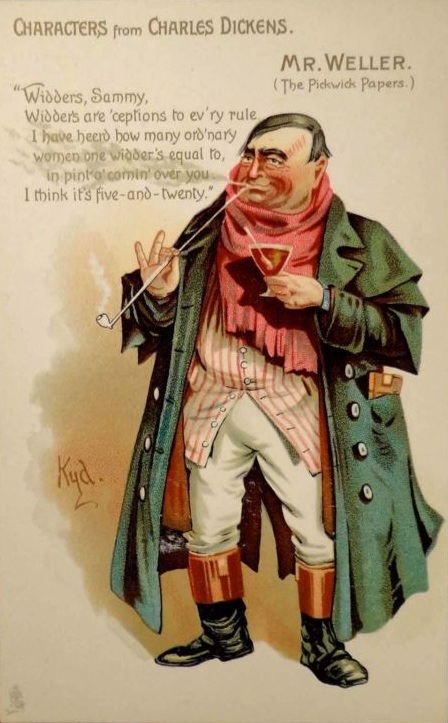

So let’s start with the Victorians. Much of what rendered the Victorian widow an exceptional figure, as Mr. Weller (see illustration on the right) proclaims in Dickens’s The Pickwick Papers (1836-37), had its roots in her identity as a single woman who was no longer under the guardianship of a husband or a father. As such, she had a social and economic independence that was granted to other women only gradually in the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. For those whose husbands left them no or very little of financial worth, this independence took a different form, namely that of destitution. Although by the 1850s life insurance had begun to be advertised as a scheme affordable by all classes of society, in reality many working-class and middle-class widows found themselves reliant on charity and the church after their husband’s death, often because life insurance was much less affordable among these groups than its champions claimed (Curran, 1993: 221).

So let’s start with the Victorians. Much of what rendered the Victorian widow an exceptional figure, as Mr. Weller (see illustration on the right) proclaims in Dickens’s The Pickwick Papers (1836-37), had its roots in her identity as a single woman who was no longer under the guardianship of a husband or a father. As such, she had a social and economic independence that was granted to other women only gradually in the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. For those whose husbands left them no or very little of financial worth, this independence took a different form, namely that of destitution. Although by the 1850s life insurance had begun to be advertised as a scheme affordable by all classes of society, in reality many working-class and middle-class widows found themselves reliant on charity and the church after their husband’s death, often because life insurance was much less affordable among these groups than its champions claimed (Curran, 1993: 221).

The 1840s and 1850s in particular saw sermons and pamphlets published that alerted religious communities to the plight of the poor widow alongside the suffering of orphans. While officers’ widows had received a war widows’ pension since 1708, the Crimean War (1853–56) saw the creation of the Patriotic Fund, dedicated to “help only ‘on-the-strength’ widows of other ranks”, and in 1885 the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Families Association was founded to help “both ‘on-the-strength’ and ‘of-the-strength’ war widows of other ranks” (Milligate & Shaw, 2011). In an appeal on behalf of the fund, Scottish cleric William Clugston reminded his congregation that “the widows and the orphans […] have strong, and direct, and just claims on the nation’s liberality. Their husbands and their fathers went forth at the command of their country, and in the service of their country they fell. Their fatherless children are left, and their widows look to the nation. Let them not look in vain” (Clugston, 1854). The impoverished war widow, then, became god’s wife and the nation’s daughter.

According to the New Poor Law (1834), widows were entitled to outdoor relief, that is, assistance in the form of money, medical services, food, and clothes, without having to enter the workhouse (Lees, 1998: 206-10). In southern England, however, this exemption did not apply to childless women who had lost their husband more than six months ago; they, if physically healthy, were deemed fit and free to work (Bloy, 2002). Throughout the remainder of the century, the rise in so-called friendly societies provided some limited additional help for those having to draw on assistance through the poor law system, including impoverished widows, but provision for their welfare remained minimal and usually inconsistent (Lees, 1998: 206). As Lynn Hollen Lees has noted, “trapped in a low-wage, limited labor market, they had to draw on multiple sources of support and be flexible in the face of personal disasters and hard times. Piecing together their private resources with some public aid kept them and their families alive” (1998: 210). For elderly widows, circumstances changed for the better with the Old-Age Pensions Act of 1908, which introduced means-tested state pensions for British men and women over the age of 70, but the younger widow’s financial situation remained dependent largely on the foresight and savings of her husband, and thus became a point of focus for feminist women’s rights campaigns.

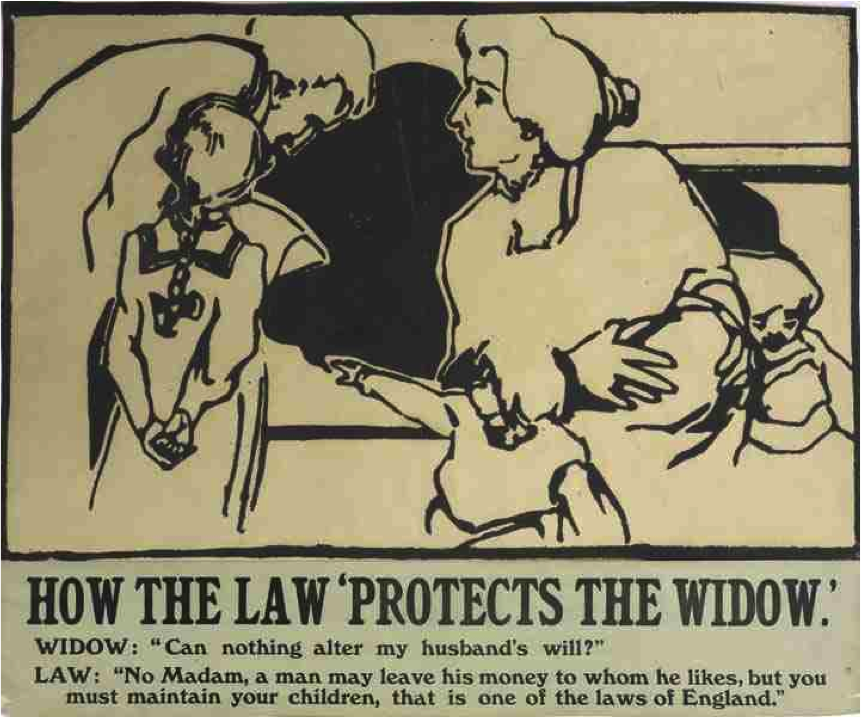

In a postcard titled “How the Law ‘Protects the Widow’” (1909), produced by the Suffrage Atelier, we witness an exchange between a representative of the law and a widowed mother of three children, a dialogue that aimed to raise awareness of the highly problematic and unequal legal obligations of a mother on the one hand, and a man on the other. “A man may leave his money to whom he likes,” the solicitor tells the widow, “but you must maintain your children, that is one of the laws of England”. Prior to the Guardian of Infants Act (1886) only illegitimate children legally belonged to the mother (and could, even if avowed the father, not be taken into possession by him); yet, the mother would be unable to claim outdoor relief for herself or the offspring (or any other, legitimate children born prior to the illegitimate child) (The Poor Law Commission, 1844: 330). A husband’s powers over a legitimate child, on the other hand, were absolute, so much so that he could appoint a guardian other than the child’s mother to care for his offspring in the event of his death. As Annie Besant put it, “the law […] ignores every claim of the mother who is also a wife” (Besant, 1878: 420). From 1886, the mother was appointed as guardian of the legitimate children once she had been widowed, but no measures were put in place to ensure she would be able to provide for her dependents without a husband’s income. Her claim to her children was acknowledged; her potential financial inability to clothe and feed them was not.

From World War I, the British government granted war widows’ pension to all war widows, be they on-the-strength, off-the-strength, or widows of volunteers. Building on the National Insurance Act (1911), which “made no provision for the care of widows and orphans, because insurance companies felt such provision would make it harder to sell life insurance” (Schmidtz & Goodin, 1998: 68). Between the World Wars, Neville Chamberlain introduced the Widows, Orphans, and Old Age Contributory Pensions Act (1925), which extended the contributory principle to pensions and “provided maintenance outside the Poor Law for widows” (Office for National Statistics, 2011: 3). But it severely limited the number of state-supported widows whose husbands had not been killed during the war, as only those who were married to insured men and widowed after 4 January 1926 were eligible for widows’ pension; the widows of insured men who had died before this date only received widows’ pension if they had children younger than fourteen, and provision would cease once their children exceeded that age. The 1929 amendment bill lifted these limitations, to a certain extent, by awarding widows’ pension also to women who were widowed before 4 January 1926, providing they were of or above the age of 55, or had children who were under sixteen years of age. Thus, younger, childless widows or widowed mothers with children older than sixteen were not eligible for widows’ pension.

From World War I, the British government granted war widows’ pension to all war widows, be they on-the-strength, off-the-strength, or widows of volunteers. Building on the National Insurance Act (1911), which “made no provision for the care of widows and orphans, because insurance companies felt such provision would make it harder to sell life insurance” (Schmidtz & Goodin, 1998: 68). Between the World Wars, Neville Chamberlain introduced the Widows, Orphans, and Old Age Contributory Pensions Act (1925), which extended the contributory principle to pensions and “provided maintenance outside the Poor Law for widows” (Office for National Statistics, 2011: 3). But it severely limited the number of state-supported widows whose husbands had not been killed during the war, as only those who were married to insured men and widowed after 4 January 1926 were eligible for widows’ pension; the widows of insured men who had died before this date only received widows’ pension if they had children younger than fourteen, and provision would cease once their children exceeded that age. The 1929 amendment bill lifted these limitations, to a certain extent, by awarding widows’ pension also to women who were widowed before 4 January 1926, providing they were of or above the age of 55, or had children who were under sixteen years of age. Thus, younger, childless widows or widowed mothers with children older than sixteen were not eligible for widows’ pension.

For war widows, conditions worsened significantly during World War II, when their pension began to be regarded as unearned income and was taxed at the highest rate of 50%, meaning many women had to deal with their grief, their children, and significantly reduced circumstances (Milligate & Shaw, 2011). In 1971, Laura Connolly, a British war widow who returned from Australia – where war widows’ pensions were tax-free – refused to pay tax and called on British war widows to stand together and take action, resulting in the founding of the War Widows’ Association (WWA) a year later (Milligate & Shaw, 2011). After incessant campaignstreing, the tax was first reduced to 25% in 1976 and was eventually lifted completely in 1979 under Margaret Thatcher. Yet, there were still significant differences in war widows’ pension income between those who lost their husbands before the introduction of the Social Security Act (1973) (Thurley, 2014: 1) and those who were widowed after. The act meant that those women widowed after 1975 would benefit from the new Armed Forces Pension scheme and “received a Forced Family Pension in addition to their war widows’ pension” if their husband had “died either in service or in retirement where death is attributable to time in the service” (Milligate & Shaw, 2011). It was not until 1990 that this disparity was addressed through a Ministry of Defence supplementary pension and that the WWA achieved its aim of “parity of pensions for all war widows” (Milligate & Shaw, 2011).

For war widows, conditions worsened significantly during World War II, when their pension began to be regarded as unearned income and was taxed at the highest rate of 50%, meaning many women had to deal with their grief, their children, and significantly reduced circumstances (Milligate & Shaw, 2011). In 1971, Laura Connolly, a British war widow who returned from Australia – where war widows’ pensions were tax-free – refused to pay tax and called on British war widows to stand together and take action, resulting in the founding of the War Widows’ Association (WWA) a year later (Milligate & Shaw, 2011). After incessant campaignstreing, the tax was first reduced to 25% in 1976 and was eventually lifted completely in 1979 under Margaret Thatcher. Yet, there were still significant differences in war widows’ pension income between those who lost their husbands before the introduction of the Social Security Act (1973) (Thurley, 2014: 1) and those who were widowed after. The act meant that those women widowed after 1975 would benefit from the new Armed Forces Pension scheme and “received a Forced Family Pension in addition to their war widows’ pension” if their husband had “died either in service or in retirement where death is attributable to time in the service” (Milligate & Shaw, 2011). It was not until 1990 that this disparity was addressed through a Ministry of Defence supplementary pension and that the WWA achieved its aim of “parity of pensions for all war widows” (Milligate & Shaw, 2011).

References

Annie Besant, [1878] “Marriage: As It Was, As It Is, and As It Should Be”, in The Sexuality Debates, ed. by Sheila Jeffreys (London: Routledge, 1987), pp. 391-445 (p. 420).

Marjie Bloy, “The Implementation of the Poor Law”, The Victorian Web (12 November 2002), Accessed: 24 July 2014. http://www.victorianweb.org/history/poorlaw/implemen.html.

William Clugston, The Widow and the Fatherless; An Appeal on Behalf of the Patriotic Fund: Being a Discourse Delivered in the Free Church of Forfar, on the Evening of October 22, 1854 (Forfar: William Shepherd and C. Laing, 1854), pp.23-24.

Cynthia Curran, “Private Women, Public Needs: Middle-Class Widows in Victorian England”, A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies, 25: 2 (Summer 1993), pp. 217-36 (p. 221).

Lynn Hollen Lees, The Solidarities of Strangers: The English Poor Laws and the People, 1700-1948 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), pp. 206-210.

Helen D. Milligate and Maureen Shaw, War’s Forgotten Women: British Widows of the Second World War (London: The History Press, 2011), n.pag.

The Poor Law Commission, [1844] “Order Prohibiting Out-Door Relief”, in The Consolidated and Other Orders of the Poor Law Commissioners, and of the Poor Law Board, with Introduction, Explanatory Notes, and Index, ed. by John Frederick Archbold and A. C. Bauke (London: Shaw & Sons, 1859), pp. 326-338 (p. 330).

David Schmidtz and Robert E. Goodin, Social Welfare and Individual Responsibility: For and Against (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), p. 68.

Djuna Thurley, “Armed Forces Pension Scheme & Preserved Pensions”, House of Commons Library (15 May 2014), p. 1.

What an incredible article on the issues of veteran’s pensions, widows and orphans. Found this trying to understand what system, if any, might have been in existence in the early part of Queen Victoria’s reign. This is a source that I am saving to study even more and truly appreciate the work and the sharing of it!

Hello,

I found this article very interesting. I was wondering if you could answer a question for me. I found a probate document for one of my ancestors, and it reads, “ADEY, Frank of 6 Bathurst Parade, Bristol, gas engine driver, died 26 June 1904, Probate Bristol 7 July to James Hobbs Bridgemaster and Joseph Thomas Ablett bridgeman; effects 159 pounds.” He left behind a widow and two young daughters. Can you offer any explanation as to why these gentlemen would receive his effects instead of his widow?

Thank you!

Hi Nadine, great to find your blog. My malaysian granny had three children to a British born Station Master in Malaya in lat 1880s. Papers said he left on a pension due to illness and died shortly after. The two never married. Do you know anything about the situation for women in the colonies? Would she have been entitled to his pension even if they had married? I was told not likely.

Hello! Lovely to find someone who might be able to answer my question… I am researching the life of a Victorian mother and daughter; the father (a solicitor) died when the mother was about 52, not leaving them well-off. In one census she’s listed as an ‘annuitant’ so I presume was in receipt of some form of pension. In the 1880’s mother and daughter spend a few years in New Zealand. The daughter works a bit as a nurse, but frankly I’ve no idea how they survived, besides a lot of sponging off the better-off. As an ‘annuitant’ do you think that implies the mother really did receive a regular pension? And do you know the mechanics of getting it (did she have to go regularly to a bank/post office?) – and any idea if this would have been possible in NZ, or would they have travelled there with a bunch of cash stuffed in a mattress? Sorry for all the questions – any ideas/pointers much appreciated!!! Thanks.

Hi Kate! This sounds exciting – thanks for finding the blog. 🙂 If she was an annuitant, and especially if her husband was a solicitor, this means she would have received an annuity that was either stipulated in his will and came from his estate, or part of a “life assurance (later life insurance”) policy he took out. Life assurance seems to have started to be advertised around the 1860s. Is there any chance you can find a record of his will? The annuity would have been paid either by the insurance company or by the person (solicitor) who was appointed to manage his estate. Hope this gives you an idea? This would explain why they could afford to get by on only some work.

Hi, thanks for the speedy reply! I did have his (rather hard-to-read will) … https://victoriankatemarsden.wordpress.com/1873/08/04/kms-father-dies-2/ & I don’t think mentions any form of annuity, but you’re right that he might have had a life assurance policy too; or presumably his widow could have purchased an annuity with the estate proceeds. I’m still a bit puzzled as to how that might have been paid if she were abroad (even in the colonies where sterling was used then) in a day without electronic funds transfers … will carry on looking!! Thanks. Kate.

Would a woman whose husband was torpedoed in 1917 while working on a commercial ship receive a widows pension? Would this be a war pension or ordinary widows and orphans pension. She had a child aged two.

Hi Marion. War widows’ pension was only granted to those who had been married to men in service (including volunteers), and even then there were very tight restrictions which meant many war widows weren’t eligible (e.g. if their husband died of a disease while in service, or if their death could in any way be attributed to negligence). So if the husband you’re referring to was not in service, she definitely wouldn’t have qualified for war widows’ pension. A state pension for widows whose husbands weren’t killed in service was only introduced in 1925, and the woman you refer to would not have qualified for this until 1926. So since she wasn’t classed as either a war widow or as being of old age, she would have had to rely on her husband’s will (though, if he had one, he was perfectly free to leave his money to whoever he wanted), charitable organisations (who judged a woman’s worthiness of help by how she raised her children, kept her household, and conducted herself as a single woman), and the Poor Law. It was a very difficult time for widowed women, even if they were war widows and could potentially be entitled to a war widows’ pension. Does this answer your question? If not, please let me know if you have any more detail and I’ll be able to look into this more closely for you.